‘Traditional network fabrics are ill equipped to deal with the performance and scale requirements demanded by the rapid emergence of Generative AI (Gen-AI)’.

That’s the common refrain… but hang on a minute, my current network infrastructure supports every other workload and application so what’s the problem? In fact my current infrastructure isn’t even that old! Why won’t it work?

To understand why this is the case we need to take a quick 10000 foot overview of what we typically have in the Data Center, then let’s layer some AI workload ( GPU’s everywhere!) on top and see what happens. Health warning… This isn’t an AI blog, like everybody else I am learning the ropes. Out of curiosity, I was interested the above statement, and wanted to challenge it somewhat to help me understand a little better.

First things first, a brief synopsis of the Enterprise Data Center fabric in 1000 words or less an 2 diagrams. I do make the bold assumption, that those reading this blog, are at least familiar with the basic spine/leaf fabrics that are pretty ubiquitous in most enterprise Data Centers.

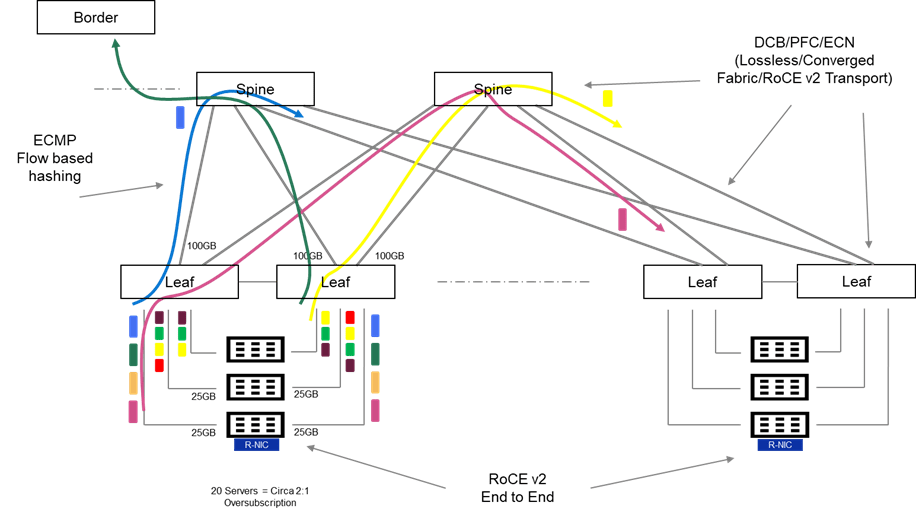

The Basic Spine/Leaf Topology

I do like a diagram! Lots going on in the above, but hopefully this should be relatively easy to unpack. There is quite a bit of terminology in the following, but I will do my best to keep this relatively high level. Where I have gone a little overboard on an terminology PFC, ECN, ECMP, i have done so with the intent on following up on the next post, where I will overview some of the solutions.

Typically we may have:

- Many Heterogeneous flows and application types. For example, Web Traffic bound to the Internet via the network border (Green Flow), Generic Application Client Server Traffic inter host (Purple Flow) and perhaps loss/latency sensitive traffic flows storage, real-time media etc. (Yellow Flow)

- These flows generally tend to be short lived, small and bursty in nature.

- The fabric may be oversubscribed at of a ratio of 2:1 or even 3:1. In other words, I may have 20 servers in a physical rack, served by 2 Top of Rack Switches (TOR). Each server connecting at 25Gbps to each TOR. (Cumulative bandwidth of 500GB). Leaf to Spine may be configured with 2 X 100Gbps, leaving the network oversubscribed at a ratio of circa 2.5:1.

- Intelligent buffering and queuing may be built in at both the software and hardware layers to cater for this oversubscription and mitigate against any packet loss on ingress and egress. One of the key assumptions here, is that some applications are loss tolerant whilst others are not. In effect, we know in an oversubscribed architecture, we can predictably drop traffic in order to ensure we protect other more important traffic from loss. Enhanced QoS (Quality of service) with WRED (Weighted Random Early Detect), is a common implementation of this mechanism.

- Almost ubiquitously, ECMP (Equal Cost Multipath Routing), which is a hash-based mechanism of routing flows over multiple equally good routes is leveraged. This allows the network, over time, load balance effectively over all available uplinks from leaf to spine and from spine to leaf.

- The fabric can be configured to enable lossless end to end transmission to support loss intolerant storage-based protocols and emulate the capabilities of Fiber Channel SAN and InfiniBand leveraging Data Centre Bridging (DCB), Priority Flow Control (PFC) and Explicit Congestion Notification (ECN).

- RDMA (Remote Direct Memory Access) capability can be combined with lossless ethernet functionality, to offer an end-to-end high performance, lossless, low latency fabric to support NVME and non-NVME capable storage, as well as emerging GPUDirect Storage, distributed shared memory database and HPC/AI based workloads. This combined end-to-end capability, from server to RDMA capable NIC, across the fabric, is known as RoCE (RDMA over Converged Ethernet), or in its most popular iteration, RoCE v2 (routable RoCE). ( Spoiler: This will be part of the solution also!)

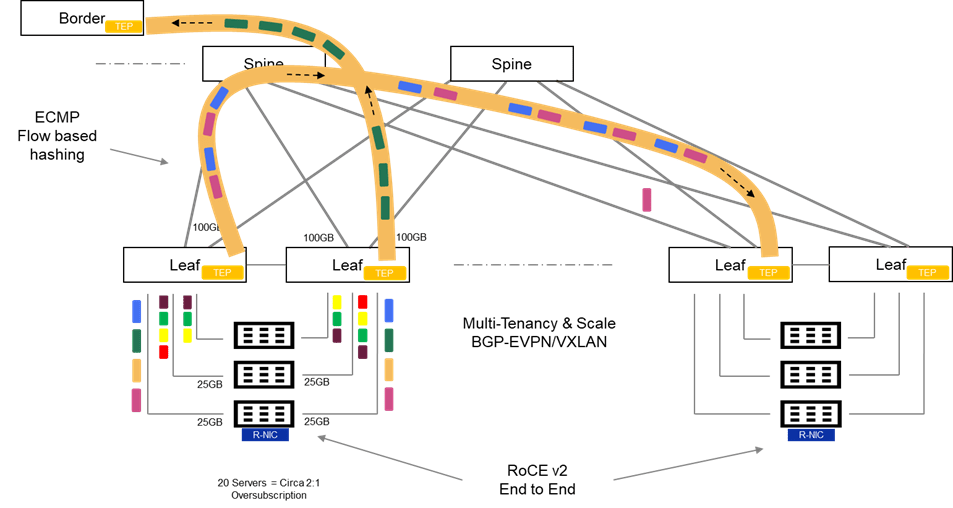

What about Scale and Multitenancy?

In general, enterprise grade fabrics require more than just spine/leaf to deliver feature richness in terms of scale, availability and multi-tenant capability in particular. Enterprise fabrics have evolved over the last number of years to address these limitations primarily leveraging BGP-EVPN VXLAN. Whilst considerably beyond the scope of this post, this family of features introduces enhancements to the standard spine-leaf architecture as follows:

Scale and Availability leveraging VXLAN

- VXLAN (Virtual Extensible LAN) as opposed to VLANs. Unlike traditional VLAN networks, which are constrained to circa 4096 VLAN’s, VXLAN can theoretically scale up to 16 million logical segments.

- Layer 2 adjacency across the fabric with VXLAN/VTEP tunnelling and distributed anycast gateway. VXLAN encapsulates layer 2 frames within UDP and tunnels payload across the network. Distributed gateway makes the networks IP gateway available across the entire fabric. This feature is a fundamental enabler to allow virtual machine IP address preservation, in the event of VM machine mobility across the fabric (e.g. VMware vMotion)

- Failure domain segmentation via Layer 2 blast radius isolation: The Layer 2 over layer 3 VXLAN tunneling technique limits the propagation of Spanning-Tree L2 domains to the local TOR. Without such a technique there is no scalable mechanism to limit the fault propagation on one rack, polluting the entire network.

Multitenancy with MP BGP EVPN ( Multi-Protocol Border Gateway Protocol)

As an extension to the existing MP-BGP, MP-BGP with EVPN, inherits the support for multitenancy using the virtual routing and forwarding (VRF) construct. In short, we can enforce Layer 2 and Layer 3 isolation across individual tenants, whilst leveraging the same common overlay fabric. This has made this technique very popular when deploying cloud networks, both public and private.

So, I’m sure I have missed a lot and of course I have skirted over masses of detail, but broadly the above is representative of most Enterprise Data Centers.

Evolution to Support Scale Out Architectures and AI

So first things first, all is not lost! We will see this in the next post, I have alluded to the above that many of the existing features of traditional ethernet can be transposed to an environment that supports GEN-AI workloads. Emerging techniques to ‘compartmentalise’ the network into succinct areas are also beneficial…again we will discuss these in the next post.

What happens the Traditional Fabric when we load up GEN-AI workload on top?

So let’s park the conversation around rail architectures, NVIDIA NVLINK, NCCL etc. These are part of the solution. For now, let’s assume we have no enhancements, neither software or hardware to leverage. Let’s also take this from the lens of the DC Infrastructure professional…. AI is just another workload. Playing this out, and keeping this example very small and realistic:

- 4 Servers dedicated for AI workload (learning & Inferencing). Let’s say the Dell XC 9680. Populated with our favorite GPU’s from NVIDIA, say 8 per server.

- Each GPU has dedicated PCIE NIC speed of 200GB.

I’m a clever network guy, so I know this level of port density and bandwidth is going to blow my standard oversubscription ratio out of the water, so I’m ahead of the game. I’m going to make sure that I massively up the amount of bandwidth between my leaf layer and the spine, to the point be I have no oversubscription. I am hoping that this will look after this ‘tail latency’ requirement and Job Completion Time (JCT) metrics that I keep hearing about. I have also been told that packet loss, is not acceptable… again .. no problemo!!! My fabric has long since supported lossless ethernet for voice and storage…

so all good… well not really, not really at all!

Training and Inferencing Traffic Flow Characteristics:

To understand why throwing bandwidth at the problem will not work, we need to take a step back and understand the following:

- AI Training is associated with a minimal amount of North-South and a a proliferation of East-West flows. Under normal circumstances this can put queuing strain on the fabric, if not architected properly. Queuing is normal, excessive queuing is not good and can lead to packet delay and loss.

- AI training is associated with a proliferation of monolithic many to many (M:M) and one to many (1:M) Elephant Flows. These are extremely large continuous TCP flows, that can occupy a disproportionate share of total bandwidth over time, leading to queuing, buffering, and scheduling challenges on the fabric. This is as a result of the ‘All to All’ communication between nodes during learning.

- The Monolithic nature of these flows leads to poor distribution over ECMP managed links between spine and leaf. ECMP works best when flows are many, various and short-lived.

If we attempt to deploy an AI infrastructure to deliver Training and Inferencing services on a standard Ethernet fabric, we are likely to encounter the following performance issues. These have the capability to effect training job completion times by introducing latency, delay and in the worst-case loss onto the network.

Job Completion Time (JCT) is a key metric when assessing the performance of the Training phase. Training consists of multiple communications phases, and the next phase in the training process is dependent on the full completion of the previous phase. All GPU’s have to finish their tasks, and the arrival of the last message effectively ‘gates’ the start of the next phase. Thus, the last message to arrive in the process, is a key metric when evaluating performance. This is referred to as ‘tail latency’. Clearly, a non-optimised fabric where loss, congestion and delay are evident, has the capability of introducing excessive tail latency and significantly impacting on Job Completion Times (JCT’s).

Problem 1: Leaf to Spine Congestion (Toll Booth Issue)

So we have added lots of bandwidth to the mix, and indeed we have no choice, but in the presence of Monolithic long-lived flows and b) the inability of ECMP to hash effectively, then we have the probable scenario of flows concentrating on a single, or subset of uplinks from Leaf to Spine. Invariably, this will lead to the egress switch buffer, on the leaf filling and WRED or tail drop ensuing. Congestion will of course, interrupt the TCP flow and will have a detrimental effect on tail latency. This is the ‘Toll Booth’ effect where many senders are converging on a single lane, when other lanes are available for use.

The non variable and long lived nature of the flow ( Monolithic), combined with the inability of ECMP to hash effectively ( because it depends on variability !) is a perfect storm. We end up in a situation where a single link between the Leaf and Spine is congested, even when we have multiple other links are underutilised, as if they didn’t exist at all! We have added all this bandwidth, but in effect we aren’t using it!

Problem 2: Spine to Leaf Congestion

Of course, the problem is compounded further one hop further up the network. ECMP makes a hash computation at the spine switch layer also, and chooses a downlink based on this. The invariability or homogeneous nature of the hash may lead to a sub-optimal link selection and the long-lived nature of the flow will then compound the issue, leading to buffer exhaustion, congestion and latency. Again, we may settle on one downlink and exhaust that link, whilst completely underutilise others.

Problem 3: TCP Incast – Egress Port Congestion

Finally, we potentially face a scenario created by a ‘Many to 1’ communication flow (M:1). Remember the M:M traffic flows of the learning phase are really all multiple M:1 flows also. This can occur on the last link towards the receiver when multiple senders simultaneously send traffic to the same destination.

Up next

So clearly we have zoned in on the ills of ECMP and its inability to distribute evenly flows across all available uplinks towards the spine and in turn from the spine towards the destination leaf. This is a per flow based ‘hash’ mechanism (5 Tuple) and generally works very well in a scenario where we have:

- A high percentage of east-West Flows, but still a large relevant proportion of North-South, to Internet, SaaS, DMZ etc.

- Many heterogenous flows that are short lived. In other words, we have many senders and many receivers. Over time, this variance, helps the ECMP hash evenly distribute across all available uplinks, and we end up with a balanced utilisation.

- A minimal amount of ‘All to All’ communication, bar traditional multicast and broadcast, which are handled effectively by the network.

Unfortunately, AI workloads are the antithesis of 3 characteristics, outlined above. In the next post we will overview some Dell Switching Platform enhancements that address these shortcomings, in addition to some clever architectural techniques and intelligence at the server source ( e.g. NVIDIA NCCL library, Rail Topology enhancements etc.)

Stay Tuned!

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed on this site are strictly my own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of Dell Technologies. Please always check official documentation to verify technical information.

#IWORK4DELL

[…] Hayes Blog discusses the challenges traditional data center networks face when handling the unique demands of […]

LikeLike